RP+M’s Long View on Additive

An AM firm benefiting from its connection to sister companies follows opportunities that require commitment to pursue.

What is the way forward for an independent manufacturer offering AM?

Adding this capability and developing expertise in it are risky, because the work that is best suited for additive involves parts that have been designed to take advantage of an additive process. The independent shop with AM might wait a long time before it sees parts like this. That is, it might wait a long time before its customers come to appreciate AM and begin to engineer their products to leverage its design freedoms.

Matt Hlavin sees a different way forward than this, a way that is more active than waiting. However, his way forward also requires a long view. He is the founder and CEO of Rapid Prototype and Manufacturing of Avon Lake, Ohio—or rp+m. (The company exclusively uses lowercase in referring to itself. Because it’s not the only firm with those initials in this space, I’ve decided to keep with that convention for clarity.) This additive manufacturing provider offers capabilities including FDM, DMLS, PolyJet and Binder Jetting, but much of its work on these machines—Binder Jetting in particular—involves parts that don’t have a market yet. Instead, much of its additive work, and much of the attention of its 15-member staff, centers on working with partners to develop the AM-enabled products that will come to market in the future.

Tangible Consulting

To be sure, there is plenty of traditional, shorter-term 3D printing work as well. This includes prototyping and short-run production for parts that will ultimately be manufactured through some other process. But even this work isn’t straightforward, says rp+m president Tracy Albers. Success involves helping the customer clearly identifying what it most wants to achieve in the prototype part.

“The priority might be strength, resolution or aesthetics,” she says. Additive can deliver any of the three. However, the ranking of priorities will determine both the choice of process and choices such as part orientation that are made within the process. As Hlavin points out, so-called 3D printing is not just “control-P.” The company’s service to customers amounts to “tangible consulting,” he says—advice on additive that culminates in an additive part.

But then, says Albers, there are also those customers that are working toward a promising new product or technology that can be realized only through AM. In many cases, these products call for some advance in AM knowledge or capability beyond what has been put into practice today, because something about the part geometry or material necessitates this leap. In these cases, Albers looks for the chance to enter into strategic partnerships so that rp+m and the customer can work together on the development, and profit together as well.

Some kind of partnership is needed because, without it, there is an incentive problem inhibiting AM’s advance. An OEM with a good idea about how to dramatically improve its product with additive manufacturing might lack the expertise to realize this idea, let alone the justification to buy the equipment for this work. Meanwhile, an additive service provider that does have the equipment and expertise would be reckless to invest in the development effort if that meant its role might be finished once the development was done. For the time being, partnerships will be as important as any other factor in enabling additive to realize its potential.

Collimators

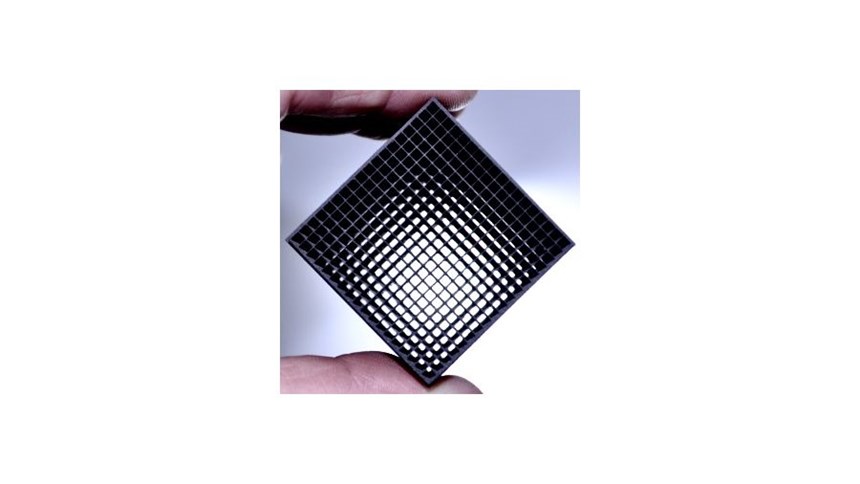

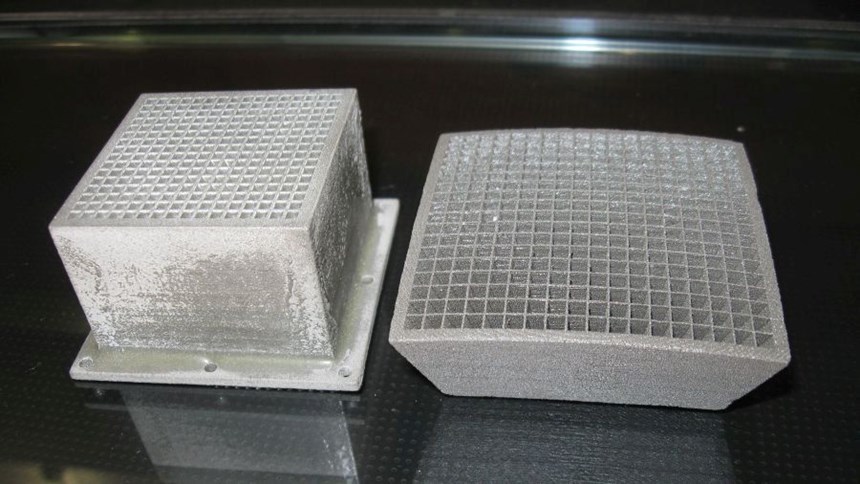

One strategic partnership is easy for rp+m to openly discuss because the partner is also owned by Hlavin. Radiation Protection Technologies (RPT) is a company he founded after learning of a tungsten-filled polymer as dense as lead (developed for a military application) that could be used as a lead substitute in medical imaging systems. The problem with applying the material to medical systems’ radiation shielding components—called collimators—is that these parts are made in quantities too low to justify mold tooling. Enter additive manufacturing. Making complex parts without molds is among the challenges AM is suited to solve.

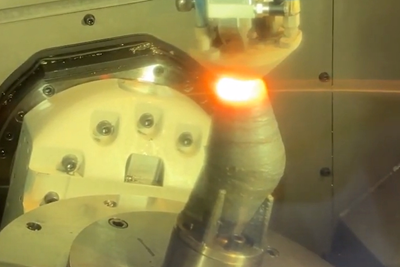

Yet not just any AM process would do. The high melting point of the material precluded a process using melting. The company instead turned to Binder Jetting, the melt-free additive process from ExOne. This process uses a liquid binder to hold the powder material (metal or non-metal) in a precise 3D shape until oven curing can harden the form. Development work related to the lead substitute began with rp+m making parts at ExOne, but now the company has an “M-Flex” machine on-site for continuing this work.

That all this work still constitutes “development” is significant, because it hints at the timeframe and forward view that the most advanced applications of AM often require. Today, lead is still an acceptable material in medical imaging. Government restrictions on lead have not applied yet in these systems, because there has not been a practical lead substitute. RPT and rp+m are using AM to realize what will be that practical substitute, but even at that, profiting from this advance once the regulations do change will require more than just printing existing parts in tungsten. Another manufacturer could do the same. The development work also includes leveraging rp+m’s additive expertise and the design freedom of additive to realize different collimator forms that function better, focusing the radiation more efficiently than the traditional forms of these components.

Foundation in Production

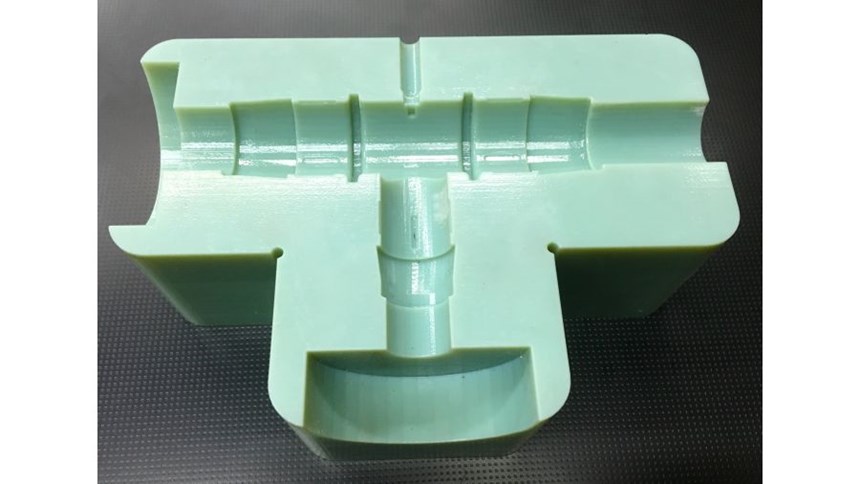

One further advantage for rp+m is vital to mention, because it is arguably the advantage that makes this kind of long-term work possible. Namely: This firm was born from an established manufacturer, another sister company—the injection molding firm Thogus. Hlavin is not the founder but instead the third-generation owner of this company. The AM firm is located in the same plant as Thogus, and the molder is an important source of steady business for the newer company.

The commitment to additive manufacturing that ultimately led to rp+m proceeded in steps. In 2009, Hlavin began to add FDM equipment at Thogus as a complement to injection molding—a way to make short-run plastic parts without a mold. From this, he learned that one of the best applications of the process was (ironically) making molds. He also learned that pursuing opportunities and developing expertise in AM required diversifying into other additive capabilities. The result was the sister company, which now serves as Thogus’s on-site supplier for prototyping and 3D-printed mold tooling. It is on the strength of this platform that rp+m is exploring the long-term possibilities of 3D printing for full production.

Right now, the Binder Jetting machine represents perhaps the company’s most promising resource for finding these long-term opportunities, the company leaders say. While all AM machines permit geometric freedom, the ability to grow parts without melting adds a range of material freedom as well.

Recently, rp+m used this capability in a project funded by NASA aimed at developing an entirely ceramic miniature gas turbine engine. When personnel from both NASA and Boeing visited, says Hlavin, they expected to see a service bureau—a small shop built around a few 3D printers. Finding an established production facility instead, they were impressed and pleasantly surprised.

That connection to production is crucial, says Hlavin, because production is where additive is heading. What his visitors saw and appreciated is that AM is being developed within and alongside an organization that already inherently understands efficiency, quality, process control and other disciplines production requires. The projects aimed at long-term applications of AM will eventually begin to bear fruit. When they do—that is, when the additive challenge is solved—then it will be time to emphasize the manufacturing of these products going forward.

Related Content

8 Cool Parts From RAPID+TCT 2022: The Cool Parts Show #46

AM parts for applications from automotive to aircraft to furniture, in materials including ceramic, foam, metal and copper-coated polymer.

Read MoreAdditive Manufacturing Production at Scale Reveals the Technology's Next Challenges: AM Radio #28

Seemingly small issues in 3D printing are becoming larger problems that need solutions as manufacturers advance into ongoing production and higher quantities with AM. Stephanie Hendrixson and Peter Zelinski discuss 6 of these challenges on AM Radio.

Read MoreThe World’s Tallest Freestanding 3D Printed Structure

Dimensional Innovations paired additive and subtractive manufacturing to create a monument for the NFL’s Las Vegas Raiders new stadium. The “never been done before” project resulted in the world’s tallest freestanding 3D printed structure.

Read More3D Printed Lattices Replace Foam for Customized Helmet Padding: The Cool Parts Show #62

“Digital materials” resulting from engineered flexible polymer structures made through additive manufacturing are tunable to the application and can be tailored to the head of the wearer.

Read MoreRead Next

Hybrid Additive Manufacturing Machine Tools Continue to Make Gains (Includes Video)

The hybrid machine tool is an idea that continues to advance. Two important developments of recent years expand the possibilities for this platform.

Read MoreAt General Atomics, Do Unmanned Aerial Systems Reveal the Future of Aircraft Manufacturing?

The maker of the Predator and SkyGuardian remote aircraft can implement additive manufacturing more rapidly and widely than the makers of other types of planes. The role of 3D printing in current and future UAS components hints at how far AM can go to save cost and time in aircraft production and design.

Read More3D Printing Brings Sustainability, Accessibility to Glass Manufacturing

Australian startup Maple Glass Printing has developed a process for extruding glass into artwork, lab implements and architectural elements. Along the way, the company has also found more efficient ways of recycling this material.

Read More