There is a duality in architecture. On the one hand, many designers feel a need to design for eternity, to strive for structures and materials that will last decades or centuries into the future. On the other, perhaps more realistic hand, tastes change.

“On average, facades change every 30 years,” says Hedwig Heinsman, cofounder of Aectual. “Interiors change every 7 years.” With this turnover in mind, it doesn’t necessarily make sense to build façades or furniture or paneling to last indefinitely. When the style shifts again, these architectural and design elements may become unwanted waste.

But rather than fighting against the tide of change, Aectual has chosen to embrace it. The Netherlands-based company uses 3D printing technology with recycled and biobased materials to create everything from table screens to flooring. While the company’s products are designed to withstand the test of time (as well as any local regulatory codes), they are also designed to support and enable recycling when they are no longer needed. Letting go of “eternity” may actually be a more sustainable and realistic way of building.

Traditional Craft and Modern Technology

Aectual spun out of Dus Architects, another Dutch firm that has been involved in 3D printed building projects for more than a decade. Circa 2012 the latter company was beginning to develop its own large-scale 3D printer, an effort that ultimately led to the creation of Aectual. (The name is pronounced “actual” — AEC is a nod to the architecture, engineering and construction industries.) Since its launch in 2017, Aectual has already completed more than 50 projects using 3D printing technology to help architects and designers automate the realization of their ideas.

Aectual’s XL 3D printing platform uses a robot arm to extrude biopolymers and recycled materials, creating architectural elements that are durable and stylish yet recyclable. Photo Credits: Aectual

The proprietary technology Aectual has created is an “XL” 3D printing system consisting of a robot arm equipped with high-capacity extruders and motion driven by ABB IRC5 controllers and Siemens PLCs. Print queue control and other built-in features are intended to help the system become increasingly autonomous. The company’s Amsterdam production facility currently operates four such robots, for a total available print area of 500 square feet.

Extruders are available to print with a range of materials, from a pelletized biopolymer made from linseed (developed in partnership with Henkel) to recycled plastic. The 3D printers are primarily used to make end-use items, but can also be used for tooling and formwork; the company regularly 3D prints forms for glass fiber-reinforced concrete (GFRC) panels and other building elements that are made by partners, a method that typically results in less material usage for both the tool and part.

The process for manufacturing the terrazzo floor in Amsterdam Schiphol Airport. 3D printed pattern lines are filled with reclaimed marble aggregate and biopolymer binder to create durable and attractive flooring.

Aectual even manufactures terrazzo flooring, which combines aggregate waste from the marble-cutting industry with biopolymer binders and 3D printed pattern lines to produce thin, durable and beautiful surfaces. This flooring is one of the least autonomous products the company creates, as it does require human craftsmanship to place the aggregate.

“It’s a combination of manual conventional technique with 3D printing,” Heinsman explains. “We are extruding more and more, but we also like to combine traditional crafts with modern technology. With 3D printing you can reintroduce the kind of craft and aesthetic that got lost after the Industrial Revolution and mass production.”

Sustainable Architecture, Reduced Waste from 3D Printing

But design possibilities were secondary to the company’s initial motive for pursuing 3D printing: getting away from waste. In conventional construction, up to 37% of all material is wasted. This, Heinsman says, is the result of standardization; if items are available in only standard sizes for an infinite variety of buildings, nothing ever fits. Almost every building material — tile, drywall, siding — will need to be cut to fit on site, resulting in scrap that must be discarded.

Through 3D printing, Aectual can instead make flooring, wall paneling, façades and even stairs to precisely fit a space, avoiding the scrap usually created in manufacturing and installation. Even better, in the case of some materials — marble aggregate, post-industrial and post-consumer plastics — Aectual is literally consuming waste from other industries to build these structures.

But what about at the end of life, when tastes shift and architectural products themselves are no longer needed? Aectual has a solution for this as well. When a customer is finished with an item and wants to make a change, Aectual will accept it back for recycling. The used material can be shredded, pelletized and used to create a new batch of 3D printed products; meanwhile, customers receive a material deposit for returning used items that can be applied to future purchases. Sustainable architecture in this case means circular architecture, not permanent.

“The material is really valuable, so it’s worthwhile for us to do this,” Heinsman says. “It’s like if you were to return a bottle to the supermarket.” The promise of a deposit incentivizes customers to turn in unwanted items rather than discard them, and the system enables Aectual to recapture used material and hold it at the same or similar value by converting it to new products.

The facade for a temporary EU building in Amsterdam (left; also pictured at the top of this article) was created by Aectual’s parent Dus Architects. When no longer needed, the facade was ground into pellets, mixed, colored and 3D printed by Aecutal into new products including the “tiny house” seen on the far right.

Of course, returning used materials to the manufacturing process is not quite as simple as substituting one feedstock for another; materials can degrade over time, and must be used in a way that makes sense. Aectual offers a full range of color options for its biopolymer, which is mixed manually for each batch. This strategy makes the material easier to recycle than plastic that has been coated or painted, but also restricts how it can be used in future batches. Recycled blue biopolymer can easily be made black, but it would be difficult or impossible to reverse that sequence.

The company’s website says that its biopolymer panels can be shredded and reprinted up to seven times, after which composting may be an option. But even better would be to reuse that material in a less demanding application such as the design lines for a terrazzo floor. “It always degrades a little bit, but surprisingly little,” Heinsman says. “If you add just a tiny bit of virgin material, that’s even better. But you can also use that material for a different function. After seven times, you can put it into a floor that will be there for the next 50 years or so.”

Scaling the System

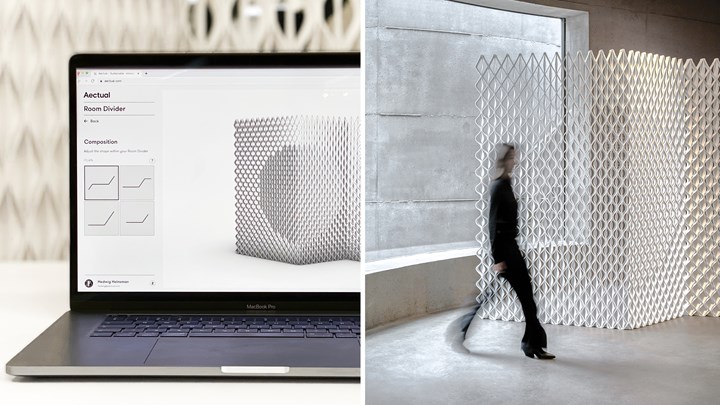

Thus far Aectual has focused on collaborating with designers and construction companies to produce architectural components and products at its Netherlands facility. That work will continue, but the company sees at least two other avenues forward aimed at making its products more accessible to customers around the world. First is opening its online store to the general public, allowing anyone to go online and custom order products like planters and room dividers.

A new online store allows anyone to order customized planters, book cases, room dividers like this and more.

Second will be leasing its proprietary technologies to other companies around the world. “It’s really a plug-and-play system, and that’s how we scale,” Heinsman says. “Our collaborators in the construction sector have a lot of experience in their different product verticals, and we have a lot of knowledge about what we do. They can lease our know-how and place our systems within their factories, which is perfect for us and perfect for them.”

One forthcoming collaboration offers an example. A Dutch company that creates temporary modular housing will be leasing an Aectual robot to directly 3D print rainscreen façade cladding on top of these units. “After five years if they change configuration or move to another building size, they can take the façade material back, shred it and reprint with a new design that fits the local conditions. It’s a perfect fit,” Heinsman says.

“You can take a different approach to how you use materials and reuse them.”

Including this leased robot, Aectual currently has five systems in the Netherlands and is preparing to open another in Dubai, which will be its first remote installation. And while 3D printing has been the primary production process thus far, Heinsman sees Aectual as a multimachine platform and expects that it will expand to incorporate other kinds of digital manufacturing strategies that enable custom architecture from sustainable materials.

“There are all these different cycles of product use in our industry, and it can be very fun when you just acknowledge that,” she says. “You can take a different approach to how you use materials and reuse them. You can say, hey, let’s change the façade every five years. Why not?”

Related Content

3D Printed End of Arm Tooling Aids Automation

Frustrations with traditional end of arm tooling led Richard Savage to start 3D printing custom versions for injection molding applications, eventually founding a company to fill this niche.

Read MoreCopper, New Metal Printing Processes, Upgrades Based on Software and More from Formnext 2023: AM Radio #46

Formnext 2023 showed that additive manufacturing may be maturing, but it is certainly not stagnant. In this episode, we dive into observations around technology enhancements, new processes and materials, robots, sustainability and more trends from the show.

Read MoreAutonomous Cobot Automation Increases Production 3D Printer Output for Ford (Includes Video)

A mobile robot that travels to each Carbon machine to unload builds lets the automaker run an additional three to four builds per machine per day. Autonomous robots fit well with 3D printing, but their role in production will extend beyond just the additive machines.

Read More500-Pound Replacement Part 3D Printed by Robot: The Cool Parts Show #50

Our biggest metal cool part so far: Wire arc additive manufacturing delivers a replacement (and upgrade) for a critical bearing housing on a large piece of industrial machinery.

Read MoreRead Next

How 3D Printing Enables Sustainability in a High-Turnover Consumer Market

Pengraff UK built its business initially providing mounting solutions for routers and telecommunications equipment, hardware with built-in obsolescence. 3D printing and sustainable materials enable the company to live its values while manufacturing products with a limited lifespan.

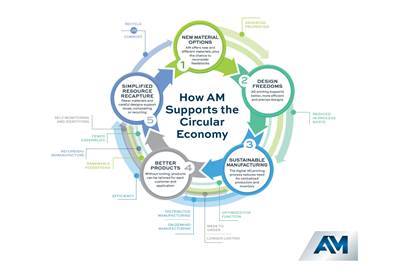

Read MoreInfographic: How Additive Manufacturing Supports the Circular Economy

This downloadable infographic illustrates how 3D printing can be applied for more sustainable manufacturing through every stage: Material, Design, Manufacturing, Product and End-of-Life.

Read More3D Printed Prefab Homes, Made from Composite and UL-Certified

Mighty Buildings wants to change the construction industry with prefabricated houses 3D printed on demand from thermoset polymer composite. Two such buildings have already been installed.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)