For additive manufacturing (AM) to win serial production work it must compete on cost and deliver on quality. But it must also do so within the right niches. One of Aerosport Additive’s current niches is vents like these for aircraft, where the quantities and complexity of the parts make AM a better production process over injection molding.

“Additive manufacturing isn’t going to replace injection molding — they are going to live in the same world,” says Geoff Combs, principal at Aerosport Additive. The natural question then might be: Where does additive stop, and where does injection molding (or machining, or some other process) take over? But this isn’t entirely the right question because it implies that production will always move to one of these other processes, an assumption that is no longer true given maturing 3D printing technologies. Instead, the right question today might be: Where does additive manufacturing (AM) win for serial production?

This is a query that Aerosport Additive is facing on a near-daily basis. Jobs that come in because of the company’s production 3D printing capabilities might be prototyped this way but turn out to be better suited to machining, urethane casting or injection molding. Meanwhile, parts that the customer imagines will be made conventionally might turn out to be a better fit for 3D printing given the volumes or lead time required. And (consistent with the assumption above) many part numbers that the company might 3D print initially do go on to be made in higher quantities through a more conventional process.

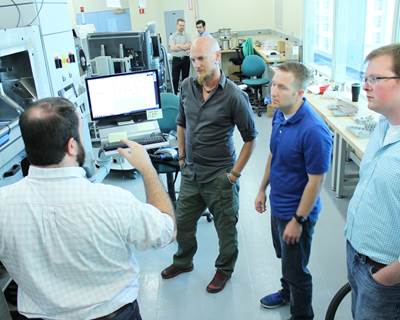

Geoff Combs (right) shows me around the new additive manufacturing wing at Aerosport Additive. The investment in this new space is reflective of the company’s aim to capture — and keep — more serial AM production work.

"We are very successful at short-run and bridge production with 3D printing," Combs says. Today, much of that production effectively leaves AM after a 3D printed run, headed for injection molding or another process for higher volumes. Going forward, Aerosport expects to hold onto that work, and continues to expand with an eye toward capturing more serial additive production — printing recurring jobs which will continue to be made additively for a long time. This aim will not be realized by increasing volumes alone, but by cultivating and winning more work suited to the processes, materials and finishing capabilities this additive manufacturer can offer.

From Model Shop to Additive Manufacturer

Located in Canal Winchester, Ohio, Aerosport Additive is a model shop-turned-additive manufacturer that still offers services connected to its origin, ranging from prototyping through hand finishing. As a model manufacturer, the company was originally known as Aerosport Design and Modeling — the “Additive” was incorporated in 2020 to reflect the growing significance of this part of the business. Production additive manufacturing accounts for about 25 to 30% of the business’s income today, with the rest coming from a mix of prototype 3D printing, CNC machining and urethane casting.

Although Aerosport adopted its first SLA 3D printer for modeling in 2002, the company didn't make the leap to production 3D printing until 2017, with the installation of its first Multi Jet Fusion system from HP. Today the company’s primary production AM capacity is its two MJF machines plus a Carima Tool digital light processing (DLP) 3D printer and its newest machine, an Xtreme 8K DLP printer from Envisiontec. All three are located in the company’s additive manufacturing wing, a recent addition to the building completed in 2020, pictured above. It also maintains a room in the original facility dedicated to stereolithography and DLP 3D printers, seen below.

Aerosport maintains three Viper Si stereolithography machines from 3D Systems for smaller prints used for urethane casting forms, prototypes and more, as well as this large-format UnionTech printer for larger quantities or bigger prints, like the pattern for a foam seat seen here. A Carbon M2 and washing station in the same area are targeted more for prototyping with an eye toward additive production.

The 3D printing capacity, however, tells only about half the story — if not a little less. “Postprocessing is more labor-intensive than building the part,” Combs says. That dynamic can be seen in the additive wing, where the machines for depowdering, bead blasting, shot peening, resin removal and vapor fusing outnumber the production 3D printers. A dye station that the company developed itself rounds out the postprocessing capacity; even after testing other automated dyeing solutions on the market, Aerosport employees prefer this solution for its quality, easy of use and speed — only about 15 minutes per cycle.

Postprocessing at Aerosport Additive

All of the choices about equipment types and materials have been made intentionally, with an eye toward meeting the needs of the market. The Carima printer was added while Aerosport was working with Adaptive3D to beta test the company’s Shore A 30, 70 and 90 resins, rubber-like materials that Aerosport expects to open opportunities in cases where flexibility is critical.

The upper level of the additive manufacturing wing is occupied by the company’s newest machine from Envisiontec and a Carima Tool 3D printer. Both are top-down style DLP systems that make it possible to print viscous elastomeric resins. (The tall parts near the back of the table are 3D printed fixtures used to clean uncured resin from parts using the honeyspinner seen in the slideshow above.)

But what isn’t here says just as much about current production applications as what is. Although new material options have been introduced for the MJF platform including TPU, TPA and PP, there hasn’t been enough demand yet for Aerosport to justify adding these materials to its portfolio. The same with full-color 3D printing; at one point it seemed like this would be the next move for the company’s AM capacity, but so far, “Color hasn’t been the hang-up we thought it’d be,” Combs says.

In short, Aerosport Additive has the 3D printing knowledge, technology and materials to make end-use production parts. It has the equipment and know-how to clean, finish and dye them. And for the scale and variety of parts it is producing right now, the company is well-equipped to handle the demands of AM production. But to capture more repeatable, serial production work for its additive manufacturing capacity there are other ways that the company aims to expand and grow.

The Hurdles to Serial Production

Today, the challenges that Aerosport Additive faces in winning serial production work for AM mostly have to do with volume, cost and customer education. To consider each in turn:

1. Managing Increasing Volumes

With the equipment and staff it has in place right now, Aerosport Additive’s sweet spot for serial AM is in the range of 2,000 to 10,000 parts per year. Its Multi Jet Fusion printers run full batches unattended seven nights a week, plus quarter- or half-sized batches during the day when employees are present to remove completed builds. Six build units allow for rapid changeover between print jobs and one postprocessing station has so far been enough to handle this work.

Higher volumes can be accomplished today with some careful planning. One of the company’s key additive manufacturing customers for instance is an industrial equipment manufacturer, for which Aerosport produces several part numbers. The customer orders up to 12,000 of one of these parts per year, but rather than produce batches on demand, Aerosport keeps about a three-month supply in inventory. With 3D printing, this inventory level is simple to maintain for these parts, because they are small enough to pack in around other builds and print continually as other builds allow.

Combs lifts a bag full of production parts for an industrial equipment manufacturer. These small parts are packed in around other jobs in the MJF printers, allowing Aerosport Additive to continually produce them so that a 3-month supply is always available for the customer.

But even so, the company is now at a point with all of its AM production work that one more serial production job at the magnitude of this one will necessitate another Multi Jet Fusion machine, Combs says. The building is ready; there is room for up to six of these printers to stretch in a line across the AM wing, so space is not a challenge. What might be, however, is scaling the postprocessing and employee needs around this added capacity. Yet adding equipment will be a necessary step to supporting greater scale, even as 3D printing technology advances further in its productivity.

A juxtaposition of production AM: Although the 3D printing step is a digital, largely automated process, parts often require many more touches once they leave the printer.

2. Competing on Cost

"The main fight that we have is cost," Combs says. For now, quantities above 30,000 parts are typically too expensive to produce through 3D printing so Aerosport focuses on smaller volumes. At this scale, switching a part intended for injection molding to AM can often be cost-effective just by virtue of avoiding tooling, but the cost calculation has to account for all the pieces of the process. For example: Additive might make it possible to deliver what would otherwise be a complex assembly of molded parts as one piece, but the as-printed surface finish won't be as smooth. If that surface needs to be cleaned, vapor finished and painted to meet the customer requirements, then additive manufacturing may turn out to be more complicated and costly than conventional injection molding which might produce the desired surface finish at the same time as the part’s geometry.

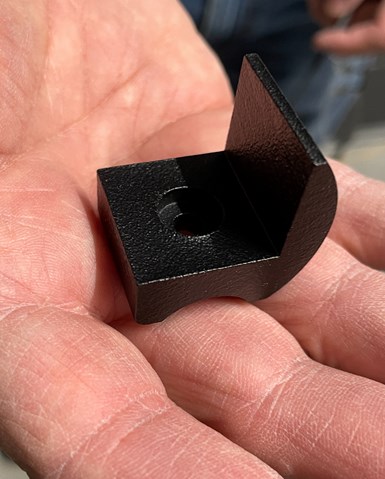

Small parts like this one can be packed in around larger ones inside an MJF build, reducing the price per part across the batch and contributing to more consistent thermal behavior throughout the print. This part was shot peened and dyed using Aerosport’s in-house dyeing system.

Part of Aerosport Additive’s strategy to reduce the cost of its 3D printed production runs is to plan builds that include a variety of parts — for instance, packing small parts for ongoing jobs in as “fillers” around other larger parts. The more densely packed the build volume, the lower the cost of all the parts in the batch. A fuller build also contributes to better print quality as a result of more consistent thermal properties across the envelope — a benefit to the manufacturer as well as the end customer.

But again, the manipulation of individual builds can only go so far toward capturing new serial production work for additive. Over the long term, AM will need to win by providing more complexity — and therefore more value — to the customer, without introducing extra work or cost. The components for the industrial equipment supplier for instance contain several undercuts that would have been complicated to mold, but add no difficulty to the printing. Consolidated parts that reduce assembly without adding other steps to the manufacturing process are another possible win; Aerosport Additive also produces an air valve with moving gates that can be printed in just one piece, replacing a riveted aluminum assembly.

This air vent assembly was previously built by riveting aluminum components together, resulting in valves that didn’t fully seal against the inner walls of the tubes. 3D printing enables this assembly to be printed in one go, and provided the ability to add a rim inside each tube to prevent leakage.

“Where 3D printing can consolidate many parts down to one, that’s where it really shines,” Combs says. “Customers see you can build things that you can’t build on a regular mold tool.”

3. Educating Customers

Teaching clients and potential clients about additive manufacturing is perhaps the most difficult and longest-term challenge Aerosport Additive is facing. In one case, an RFQ came in for an automotive assembly that could have easily been made additively, except for the material. Aerosport recommended Multi Jet Fusion with one of the nylons available for this platform as an alternative that would meet the application requirements, but the customer insisted on ABS. In the end, Aerosport machined the parts from ABS stock. Despite the recent advances of the technology and introduction of production-ready materials, additive still faces skepticism compared to the processes and materials that buyers are used to.

“The assumption that injection molding is ‘production’ has been hard to overcome,” Combs says. In these cases prototyping through 3D printing can be an avenue to convincing potential customers of its capabilities; a successful prototype can go right into production on the same printer and in the same material, without the delays and costs associated with tooling.

The Right Person at the Right Time

Aerosport Additive won’t necessarily have to overcome all of these hurdles alone. Industry advances in printer productivity and material selections will help in terms of meeting higher volumes and reducing costs. The company plans to add a second Envisiontec printer to support more applications of Adaptive3D’s ToughRubber flexible material soon (both suppliers are now part of Desktop Metal); these printers will bring greater throughput for DLP parts that may help to advance the scale of these applications. And customer awareness and understanding of additive manufacturing is growing, which may help bring in more production work suited to this process.

The key now is finding the niches where this production option makes sense — and the discovery still entails some element of luck. “Getting the right fit is the biggest challenge,” Combs says. "You’ve got to talk to the right person at the right time.”

Related Content

Understanding HP's Metal Jet: Beyond Part Geometry, Now It's About Modularity, Automation and Scale

Since introducing its metal binder jetting platform at IMTS in 2018, HP has made significant strides to commercialize the technology as a serial production solution. We got an early preview of the just-announced Metal Jet S100.

Read MoreAluminum Gets Its Own Additive Manufacturing Process

Alloy Enterprises’ selective diffusion bonding process is specifically designed for high throughput production of aluminum parts, enabling additive manufacturing to compete with casting.

Read MoreAdditive Manufacturing Is Subtractive, Too: How CNC Machining Integrates With AM (Includes Video)

For Keselowski Advanced Manufacturing, succeeding with laser powder bed fusion as a production process means developing a machine shop that is responsive to, and moves at the pacing of, metal 3D printing.

Read MoreLarge-Format “Cold” 3D Printing With Polypropylene and Polyethylene

Israeli startup Largix has developed a production solution that can 3D print PP and PE without melting them. Its first test? Custom tanks for chemical storage.

Read MoreRead Next

Polymer 3D Printing for Production, in a Pandemic and Beyond

Production 3D printing soared in 2020, brought about by supply chain shortcomings and needs related to the pandemic. More than a year later the scene is different, but The Technology House sees promise ahead.

Read More3D Printing Brings Sustainability, Accessibility to Glass Manufacturing

Australian startup Maple Glass Printing has developed a process for extruding glass into artwork, lab implements and architectural elements. Along the way, the company has also found more efficient ways of recycling this material.

Read More4 Ways the Education and Training Challenge Is Different for Additive Manufacturing

The advance of additive manufacturing means we need more professionals educated in AM technology.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)