Arcing away from Near-Net Forging

An electrical arc process joins a field of additive manufacturing technologies that could one day provide aerospace manufacturers with alternatives to near-net-shape forgings.

In the future, pounding heated metal into submission will not be the only viable means of producing certain near-net-shape aerospace components. According to various suppliers, additive manufacturing technology continues to progress toward the same standards for material strength and reliability as forging. They also claim that these freeform deposition processes take less time than forging (a matter of hours for larger components) and bring parts even closer to final geometry. By eliminating the need for tooling and reducing the time and cost required for finish-machining, these forging alternatives promise to compress the front end of the development cycle, reduce the overall production cost of aerospace structural components, and, eventually, facilitate new part designs that would not be feasible with forging.

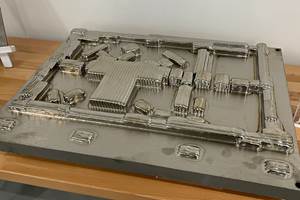

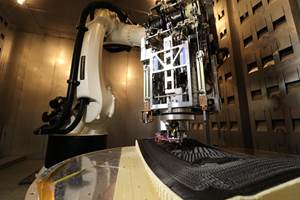

One of the most recent examples, Rapid Additive Forging (RAF) technology, offers cost savings ranging from 30 to 50 percent on various titanium parts, says Olivier Strebelle, deputy chief executive officer of strategy and business development at Groupe Gorgé, the parent company of RAF technology developer and fellow French firm Prodways. Similar to other metal deposition techniques, the deposition head and the wire material feedstock move together throughout the workzone. Unlike processes that build geometry up from beds of powder, the only restriction on part size is the travel limit of the deposition head, Strebelle says. Although final forms are not as detailed as those produced via powder-bed sintering, they’re more than detailed enough to replace forgings. Metal deposition processes are faster than powder-bed technologies, too.

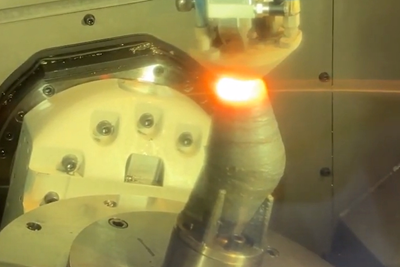

One of the primary areas in which these freeform material deposition techniques differ is the means of melting the material. RAF uses an electric arc similar to the technology employed by gas-metal-arc welding systems, and testing so far has focused primarily on titanium. The deposition head travels on a robot from Commercy Robotique, another subsidiary of Groupe Gorgé, within an enclosed atmosphere of inert gas. Initial testing shows potential speed advantages compared to laser systems because more power is available, Strebelle says. As for electron-beam sintering systems, “Our assessment is that arc-based technologies are more robust,” he continues. “This is based on our welding experience, where arc-based robots are more reliable.”

However, he emphasizes that the process is still maturing. Engineers are still working toward matching the highest standards of forged-part tensile strength, porosity and other properties. Still, they are getting close. “It could work already for parts that are not of the highest class,” he says, adding that proving the process out for flight-ready parts is likely only a matter of time. In fact, at the time of this writing, Prodways was reportedly working with an aerospace client to qualify parts that could be flying by 2019. New materials, such as aluminum and Inconel, will also undergo further testing. The company is also considering how a RAF system for production might look different than one for prototyping, and how the process might be better integrated with machining, possibly via a hybrid additive/subtractive machine. Size capabilities will most certainly expand, he says, with the next generation systems’ increasing the limit from 70-cm to 3-meter parts.

All of this work is being conducted in Europe, but Strebelle says the company could easily supply blanks produced via RAF technology from its North American headquarters in Minneapolis, Minnesota. As the process matures, he says the technology will likely follow the same path as the company’s other, mostly plastics-focused additive manufacturing offerings, with Prodways eventually moving to offer the RAF systems themselves in addition to RAF production services.

Related Content

Qualification Today, Better Aircraft Tomorrow — Eaton’s Additive Manufacturing Strategy

The case for additive has been made, Eaton says. Now, the company is taking on qualification costs so it can convert aircraft parts made through casting to AM. The investment today will speed qualification of the 3D printed parts of the future, allowing design engineers to fully explore additive’s freedoms.

Read MoreHow Norsk Titanium Is Scaling Up AM Production — and Employment — in New York State

New opportunities for part production via the company’s forging-like additive process are coming from the aerospace industry as well as a different sector, the semiconductor industry.

Read MoreHow 3D Printing Will Change Composites Manufacturing

A Q&A with the editor-in-chief of CompositesWorld explores tooling, continuous fiber, hybrid processes, and the opportunities for smaller and more intricate composite parts.

Read More8 Cool Parts From RAPID+TCT 2022: The Cool Parts Show #46

AM parts for applications from automotive to aircraft to furniture, in materials including ceramic, foam, metal and copper-coated polymer.

Read MoreRead Next

Hybrid Additive Manufacturing Machine Tools Continue to Make Gains (Includes Video)

The hybrid machine tool is an idea that continues to advance. Two important developments of recent years expand the possibilities for this platform.

Read More4 Ways the Education and Training Challenge Is Different for Additive Manufacturing

The advance of additive manufacturing means we need more professionals educated in AM technology.

Read More3D Printing Brings Sustainability, Accessibility to Glass Manufacturing

Australian startup Maple Glass Printing has developed a process for extruding glass into artwork, lab implements and architectural elements. Along the way, the company has also found more efficient ways of recycling this material.

Read More